In every Look Back, we examine a comic book issue from 10/25/50/75 years ago (plus a wild card every month with a fifth week in it). This time around, we head back ten years to June 2013 for the award-winning Hawkeye #11, where Matt Fraction, David Aja, Chris Eliopoulos and Matt Hollingsworth deliver an amazing issue that was told completely from the perspective of Hawkeye's dog.

One of the interesting things about pretty much any fictional medium is that there are so many ways to stand out and be innovative, even if you use ideas that already existed. The key is that it doesn't matter if something has been done before, because there are so many distinctive ways that any idea can be expressed. In other words, there are a whole lot of characters in the history of comic books that are riffs on Superman, but that doesn't mean that they aren't all distinctive in and of themselves, as OBVIOUSLY they are. Fawcett's Captain Marvel was clearly an attempt to do their own take on Superman, but the resulting character is still truly an original, even if he was based on Superman. People are way, way (WAY) too cynical when they say things like, "Oh, this is just Concept X mixed with Concept Y" or whatever, and, it's, like, dudes, mixing Concept X with Concept Y is, itself, an AWESOME concept!

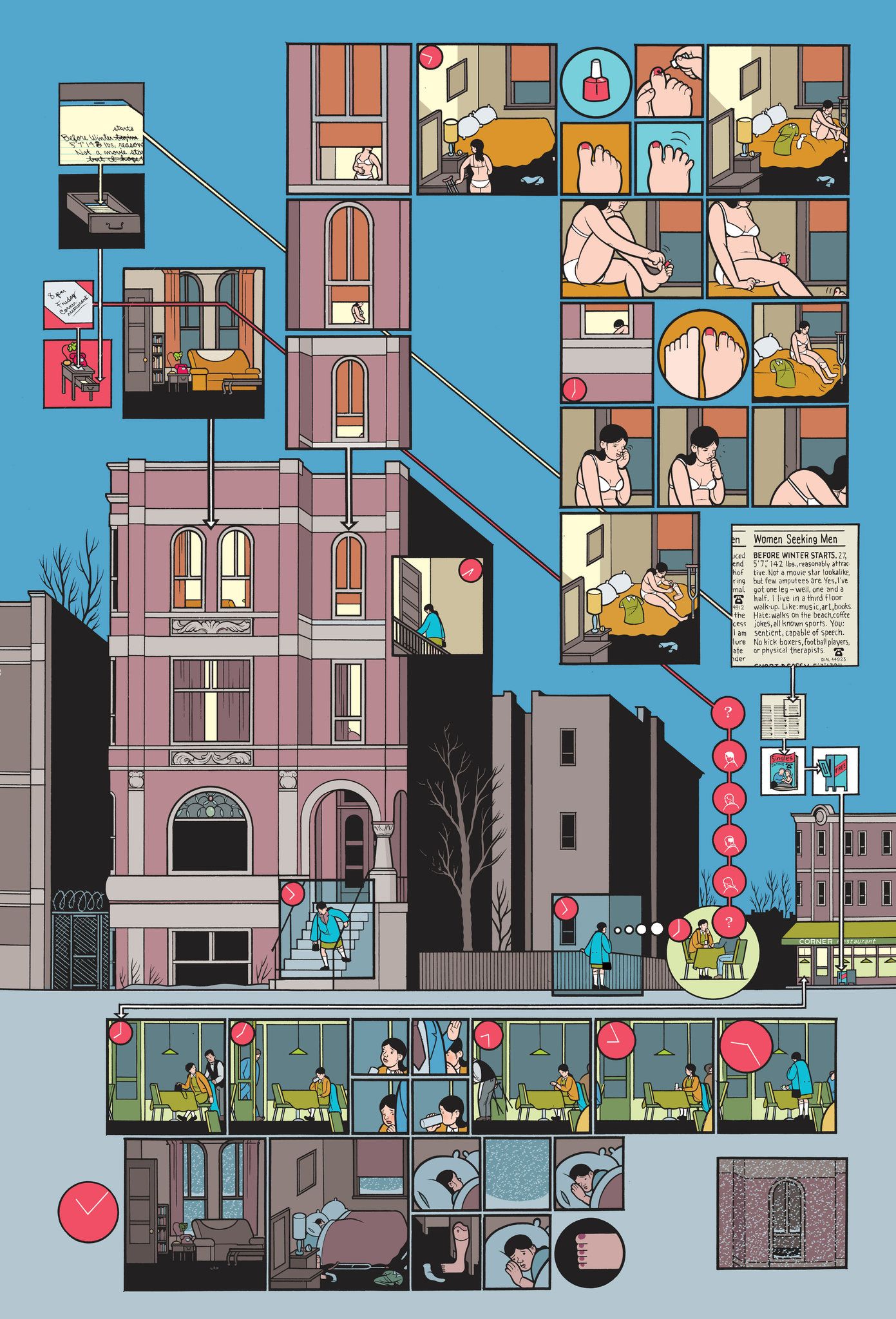

I mention this all to note that while a lot of Hawkeye #11 is evocative of the legendary Chris Ware and his wonderful Building Stories, the spin that Matt Fraction, David Aja, Chris Eliopoulos and Matt Hollingsworth do on the concept is so distinctive that it is truly its own wonderful result, as in this Eisner Award-winning story, "Pizza Is My Business," the creators took us into the mind of Hawkeye's dog and pulled off things you would be honestly shocked to see achieved with a comic book story.

What was Fraction and Aja's Hawkeye about?

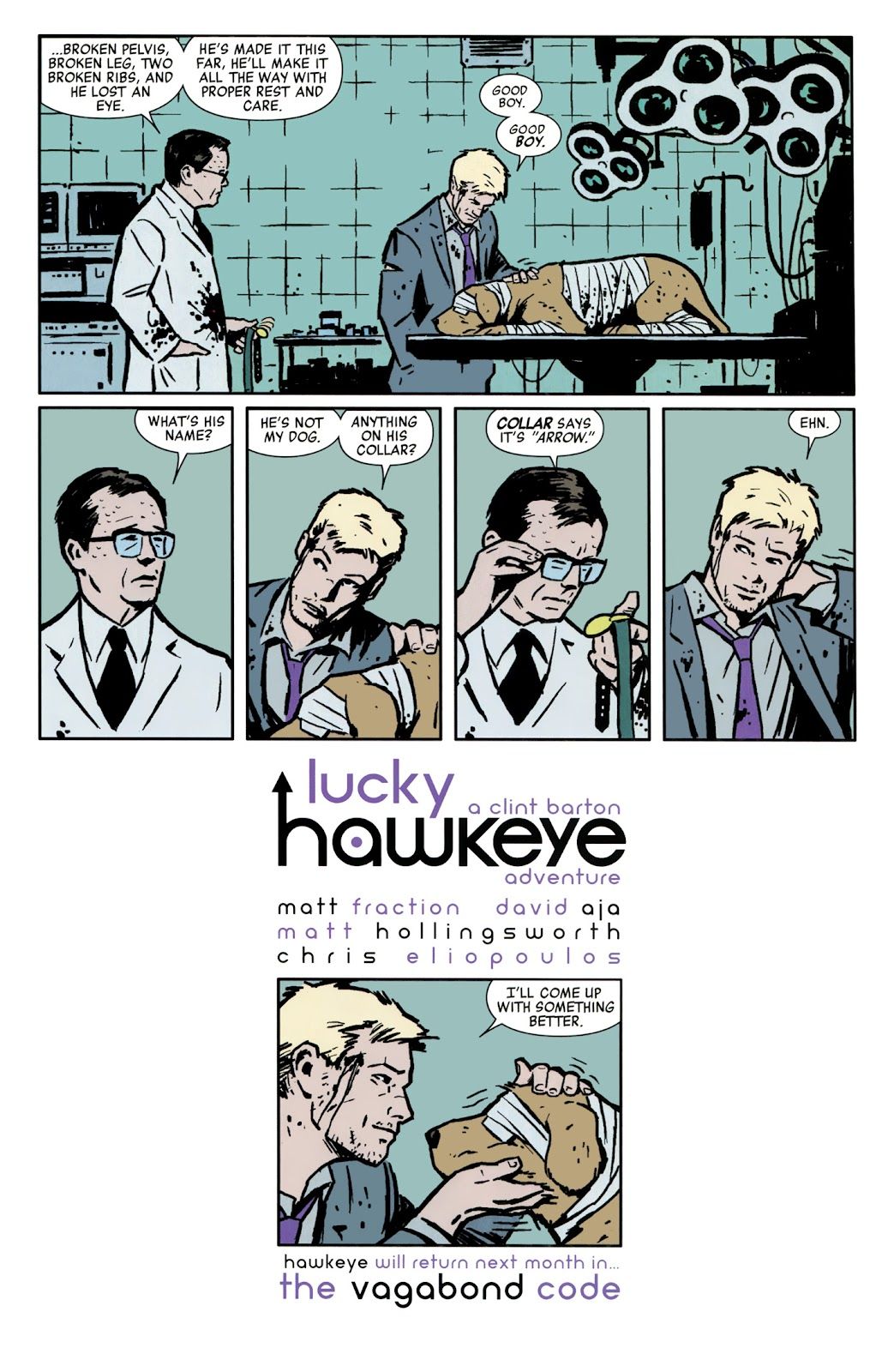

The conceit of the Hawkeye series, which launched in late 2012, was that the series would show us what Clint "Hawkeye" Barton did in his time off from the Avengers. The guys who owned his building (dubbed "The Tracksuit Mafia") were driving his neighbors out by tripling their rent, so Clint offers to pay all of their rent. This was not taken well by the Tracksuit Mafia's boss. Meanwhile, two of their goons had a dog. Clint was nice to the dog and fed it pizza. Since its owners were abusive jerks, when Clint was nearly shot by the goons, the dog attacked its own owners to save Clint. The dog was then thrown into traffic and hit by a car. Clint rushed it to a vet clinic, and then forced the head of the Tracksuit Mafia to allow Clint to just purchase the building outright.

At the end of the issue, the dog survives the surgery, and Clint learns that it is named "Arrow," but he decides to call it Lucky, instead, but fans soon just called him "Pizza Dog"...

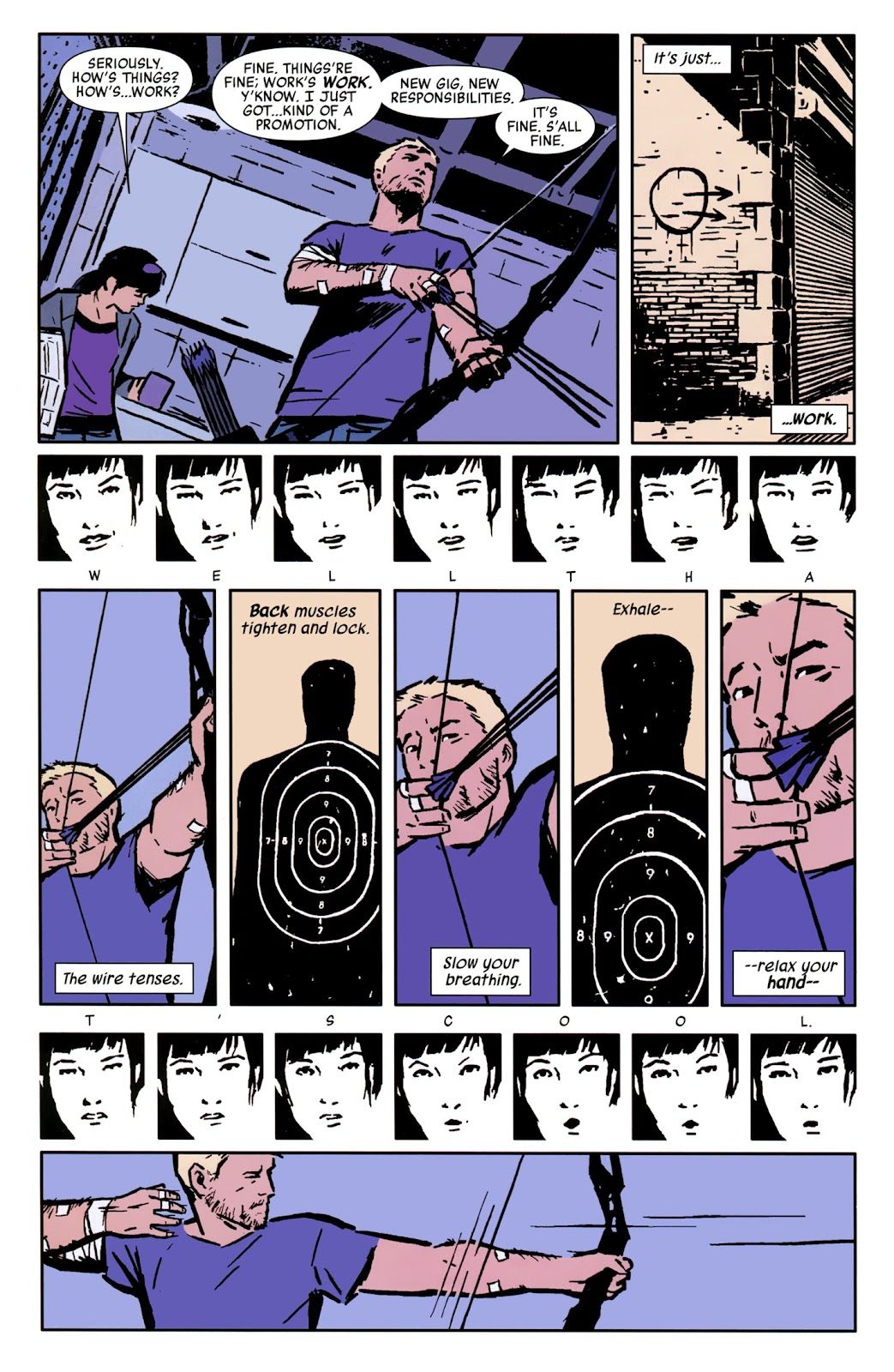

So the status quo of the comic was now Clint having to deal with the Tracksuit Mafia, who are now naturally mad at him, and so Clint has to protect the building and his now tenants. Meanwhile, he has struck up a sort of mentor/mentee partnership with Kate Bishop, a young hero also known as Hawkeye. In the second issue of the series, you can see that David Aja was putting SO MUCH DETAIL into the art for the series...

There were fill-in artists, of course, but Matt Fraction also thought it might be nice to give Aja less work to do on an issue, so he came up with an idea for a story that would allow Aja some "rest," by letting him draw less panels. The idea was to have an issue be seen through Lucky's eyes. The problem is that once Fraction started thinking more about it, it became more and more complicated. He and Aja began to brainstorm on the book, and what was meant to be a "rest" issue, was instead one of the most complicated issues imaginable!

What made Hawkeye #11 so special?

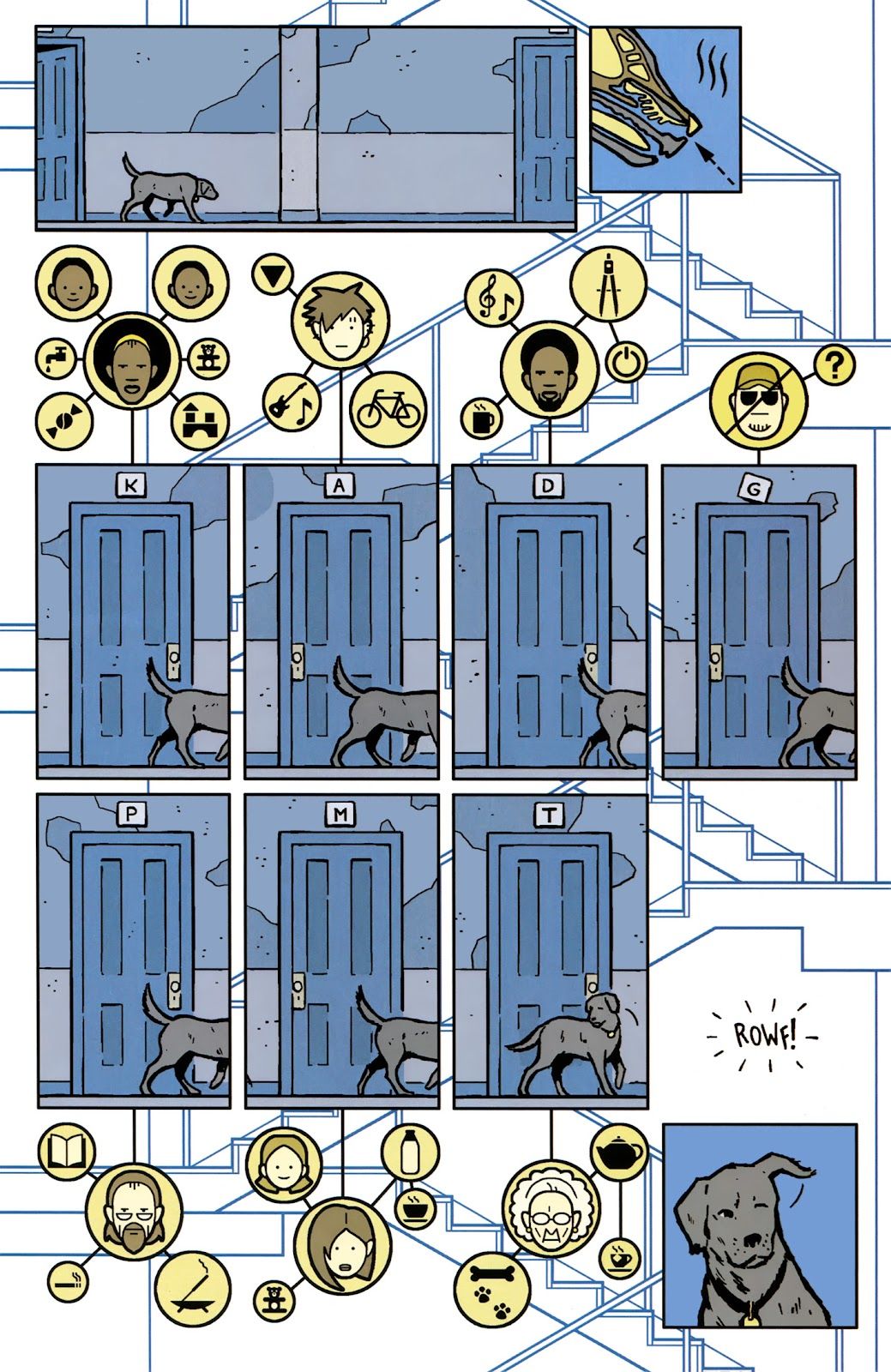

The issue was devoid of traditional dialogue, and instead was all seen from Lucky's perspective, via pictograms that show how he sees people, as each person reminds him of different things (meanwhile, the actual dialogue is all blurred, except for a few words that Lucky recognizes)...

As Lucky walks through the building, we see what he remembers about the inhabitants of each apartment in the building...

Clint Nowicke discussed the issue with Aja, who explained, "I think it was difficult in the beginning to find a visual way to show all those other senses a dog uses to interpret reality other than sight. I thought it could be a funny challenge as comics usually show reality by our sense of vision (panels) and hearing words (balloons). Once I found the way with all those infinite 2D tools we have such as pictograms, blueprints, signs… the rest was easier.

Both Matt and I decided what information was relevant, I think. Matt and I talk a lot on each issue, I cannot really tell most of the times who came with what idea, or if an idea gave the other a clue to another idea, or the idea of the idea of an idea… well, I think you know where I’m going. We decided to sign with “By” instead of “Writer-Artist” for that reason. It’s a very collaborative work."

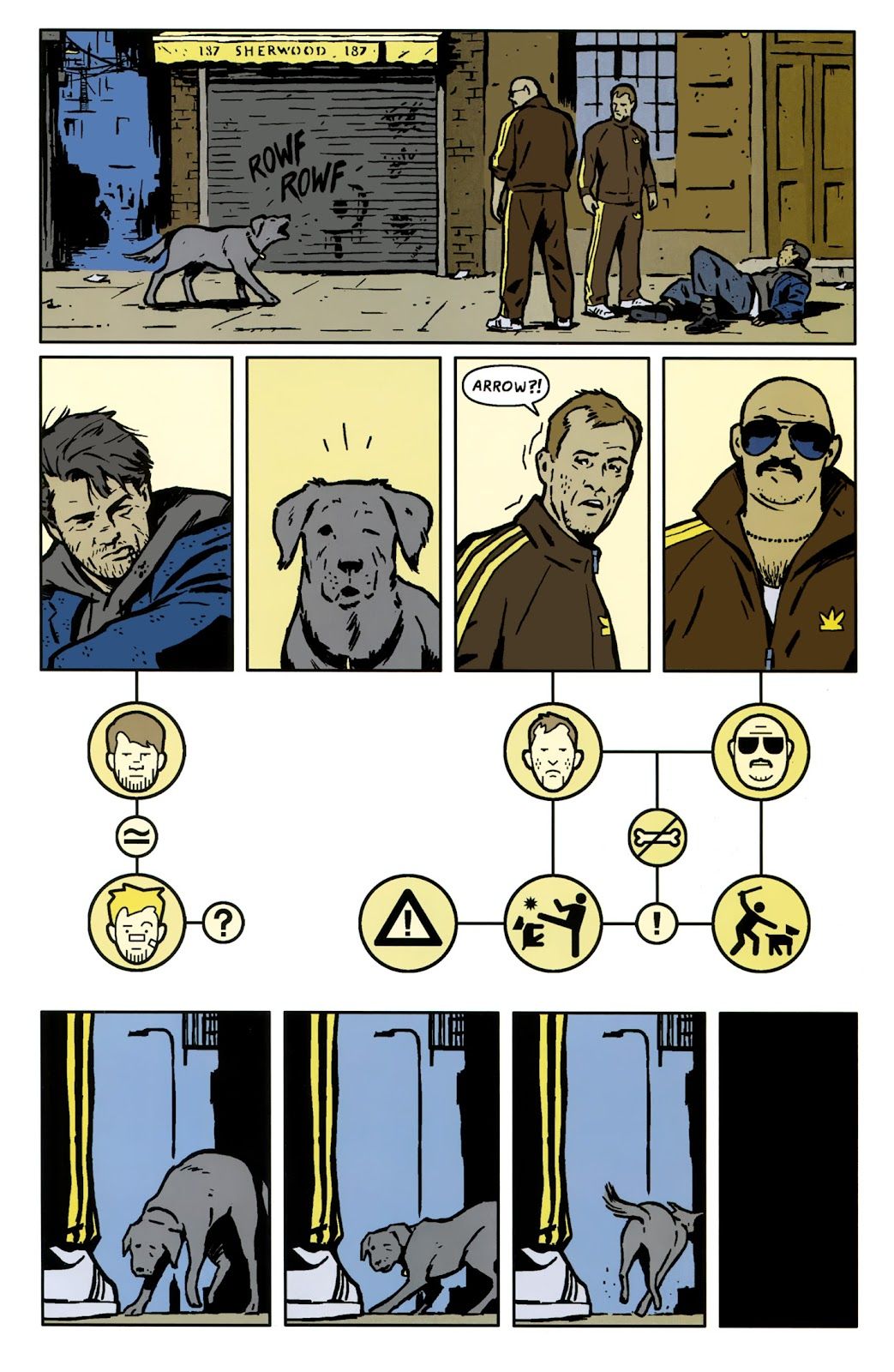

A fascinating aspect of the story (which involves a murder committed in the previous issue, that Lucky sort of "solves") is that it introduces Clint's brother, Barney, but WE don't know it is Barney, but LUCKY does (as he can tell the similarities between Clint and Barney). Meanwhile, he recognizes his old owners, and is fearful because he remembers their abuse. It's quite moving...

Another clever aspect of this comic is the fact that the events of the story are re-told from other perspectives in future issues, like we get to see all of the dialogue that we missed because Lucky can't really understand English.

As noted, this is similar to Chris Ware's Building Stories, showing the stories of, well, you know, a single building...

However, Hawkeye #11 does a lot of other things Ware didn't do, including introducing the idea of SMELL to the story, as well, via Lucky's strong sense of smell giving him direction, as well. Plus, of course, the aforementioned interconnected stories and all of the heartfelt parts of Lucky's adventure (the issue ends with the Hawkeyes splitting up as partners - and Lucky is soon not even in New York City period), so whether it was influenced by Ware or if it is just a coincidence, this story still more than stands up on its own as a strong comic book work.

If you folks have any suggestions for July (or any other later months) 2013, 1998, 1973 and 1948 comic books for me to spotlight, drop me a line at brianc@cbr.com! Here is the guide, though, for the cover dates of books so that you can make suggestions for books that actually came out in the correct month. Generally speaking, the traditional amount of time between the cover date and the release date of a comic book throughout most of comic history has been two months (it was three months at times, but not during the times we're discussing here). So the comic books will have a cover date that is two months ahead of the actual release date (so October for a book that came out in August). Obviously, it is easier to tell when a book from 10 years ago was released, since there was internet coverage of books back then.