Martin Scorsese is one of the most prolific and innovative filmmakers of the past six decades. From Mean Streets to The Irishman, the man has more medium-defining classics in any single decade of his filmography than most other filmmakers get in their entire career. So when Scorsese speaks, audiences should generally listen to what the incredibly intellectual man has to say.

This, of course, led to some outcry in 2019 when Scorsese spoke about the Marvel Cinematic Universe, saying, "I’ve tried to watch a few of them and that they’re not for me, that they seem to me to be closer to theme parks than they are to movies as I’ve known and loved them throughout my life, and that in the end, I don’t think they’re cinema." While this has led to all kinds of reactionary outrage from creators and fans alike in the year since, Scorsese is also on record saying that there is a rather notable exception to this opinion: Sam Raimi's Spider-Man films. So what makes Spider-Man Scorsese's exception?

In November of 2019, around the same time that Scorsese's interview response about the MCU went viral, Scorsese penned an op-ed for The New York Times titled "I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain." In the piece, Scorsese painstakingly deconstructs his own comments from several different vantage points and more thoroughly breaks down what he finds to be lacking in the works of the MCU. It's an absolutely phenomenal, insightful piece of writing (that everyone should check out if they haven't already) that pretty much debunks the hundreds of hot-take response pieces that have come out in the years since.

One of the core pillars of Scorsese's argument in the piece is a comparison of the MCU to the films of Alfred Hitchcock. As Scorsese says, "Hitchcock was his own franchise. Or that he was our franchise. Every new Hitchcock picture was an event," and "In a way, certain Hitchcock films were also like theme parks." Here, he draws a clear line, illustrating that the Marvel Cinematic Universe is offering grand-scaled spectacle for a wide-ranging audience, much in the same way Hitchcock's films were in the '40s, '50s and '60s.

So in Scorsese's eyes, what is the defining difference between something like Hitchcock's Rear Window or Psycho and the Marvel films? As Scorsese puts it, "(They) are stunning, but they would be nothing more than a succession of dynamic and elegant compositions and cuts without the painful emotions at the center of the story." This is what Scorsese means when he speaks of cinema: a bold, auteur-driven sense of filmic craftsmanship that is rooted in exploring deeply personal themes through the medium of moving pictures.

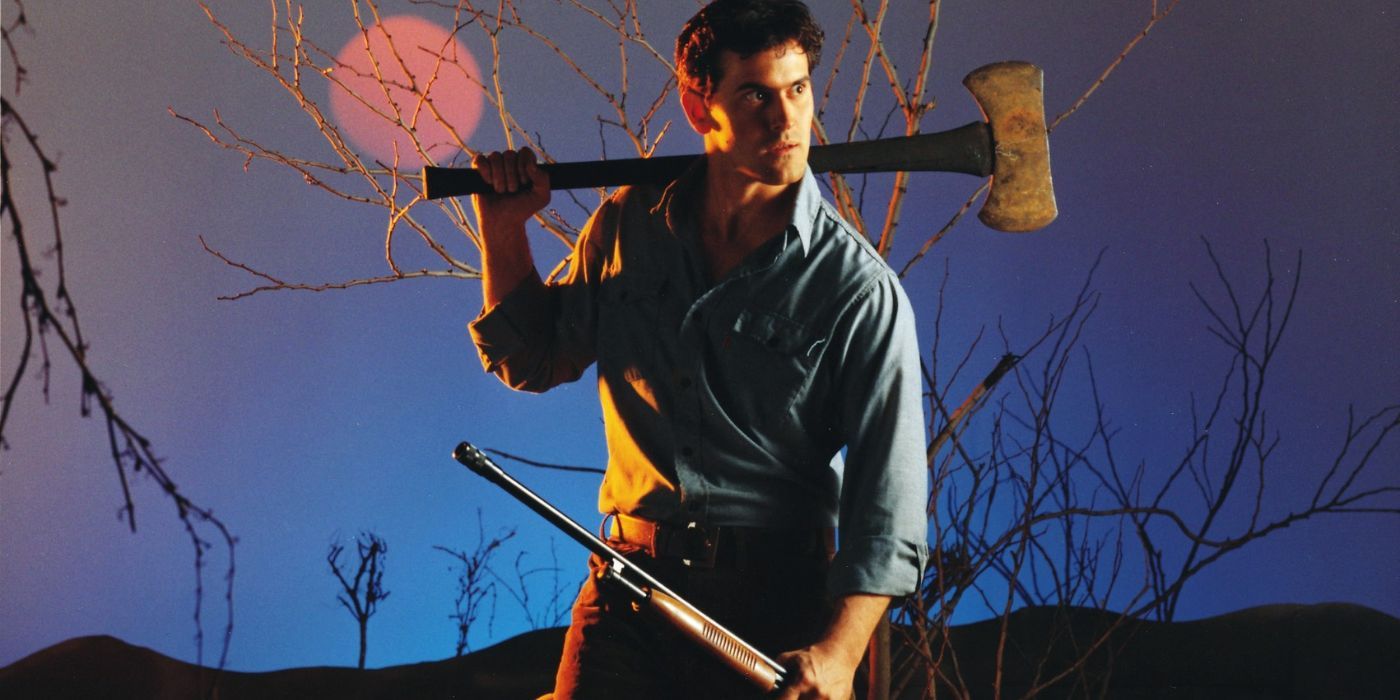

And is there any blockbuster franchise from the past 20 years that is more singularly defined by that sentence than Sam Raimi's Spider-Man films? Raimi spent an entire career showing audiences exactly what meant the most to him: tales of good people trapped in increasingly awful situations who do everything within their power to remain good and rise above evil. Sometimes they failed (A Simple Plan), sometimes they succeeded but at great personal cost (Darkman), and sometimes they seemed incapable of ever truly escaping the struggle (The Evil Dead trilogy).

Raimi explored these stories and the idiosyncratic thematic work that came with them with routinely inspired camerawork from cinematographers like Bill Pope and some of the best editing of the past few decades of cinema with editors like the insatiable Bob Murawski. Raimi loves reveling in his down-and-dirty horror roots (Evil Dead, Drag Me To Hell) but also loves slapstick comedy that dabbles in utter insanity (Evil Dead 2, Crimewave).

All of this is to say that when Raimi boarded Spider-Man in the early '00s, he brought all of himself to the table. While Raimi's Spider-Man films are very much thrilling genre works that feature tons of action and spectacle, they are also intimate works of both character and personal drive. A competition for the best scene from Spider-Man 2 would have to be between Doc Ock's tentacles surgery horror show, Spider-Man and Doc Ock's technologically innovative and emotionally-driven train fight, or the achingly intimate scene of Peter telling Aunt May of the true role he played in Uncle Ben's death.

Such is the versatility of Raimi's Spider-Man films: they are huge spectacles but also anchored in the characters and Raimi's own fundamental beliefs and interests as a filmmaker. This is undoubtedly what resonates with Scorsese. As he says, "Sam Raimi’s films I like, actually. And I’m really glad that was a big success." While he's overtly answering a question about Spider-Man, Scorsese goes out of his way to reframe his initial answer as praise not just of Spider-Man but of Raimi's body of work as a whole.

This goes hand-in-hand with something else Scorsese speaks about in his New York Times piece: the sanitation of blockbuster filmmaking in the modern age. As he explains, "Everything in them is officially sanctioned because it can’t really be any other way. That’s the nature of modern film franchises: market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption." He is undoubtedly correct here, not just about the MCU but nearly every blockbuster being made today. One need look no further for proof than a fellow 2019 release alongside Scorsese's The Irishman, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. The movie took a once explicitly auteur-driven (by George Lucas and then Rian Johnson) film series and castrated it into a soulless commercial product that attempted to please everyone and wound up pleasing no one.

Raimi's Spider-Man films were anything but "ready for consumption." They were weird, idiosyncratic works of a filmmaker that resonated with audiences, critics and Scorsese alike because of the heart and soul poured into the foundations of the spectacle and more theme park-adjacent thrills. And there are MCU films that succeed on this level as well: James Gunn's Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Ryan Coogler's Black Panther or even Raimi's own Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. But as both the MCU and blockbuster entertainment, in general, expands to more movies and more TV series, these personally-driven successes feel fewer and farther between than ever before.

.jpg)