David Lynch's 1984 version of Dune opened to scathing reviews and anemic box office. It proved such a scarring experience for the director that he famously refuses to discuss it in public. The film's reputation has improved over the years, and it has earned a cult following thanks to its striking visuals and strong ensemble. But subsequent adaptations proved superior, with the 2000 Syfy Channel miniseries more faithful and engaging even before Denis Villeneuve's masterful 2021 film changed the game.

Lynch's opinions are his own and were shaped by the experience of making the film in ways that casual viewers' aren't. The 1984 Dune was hampered by considerable production problems, as well as a visionary director whose decisions were being second-guessed. The results were bizarre and compelling but couldn't capture the soul of Frank Herbert's original novel the way that later efforts did.

Dune's Production Troubles Produced an Uneven Movie

Lynch's Dune was produced by Italian filmmaker Dino De Laurentiis, whose company released both it and Blue Velvet two years later. It made for an uncomfortable partnership. De Laurentiis hired a young auteur with a singular vision to make what he considered product. The producer's body of work is steeped in horror and science fiction, and while it includes classics such as Evil Dead II: Dead By Dawn and Kathryn Bigelow's Near Dark, it adheres to traditional tropes and storytelling techniques. Lynch's movies thrive precisely because they ignore those conventions. Without the freedom to pursue his vision, the things that make his work so compelling are lost. Lynch was ultimately denied final cut of the film, and his four-hour version was reduced to two hours for the theatrical release.

That had a huge impact on the film itself, starting with the massive loss of information that comes with such drastic cuts. The original novel of Dune is challenging in the ways many other sci-fi epics are, with a richly detailed world that new readers need time to absorb. The novel simply included appendices covering terminology, galactic politics, and the ecology of the planet Arrakis where the story takes place. None of the screen adaptations could employ such a solution, forcing them to integrate convoluted exposition into the narrative. Villeneuve proved extremely adept at conveying numerous details visually, with an extended running time to space it all out organically. The 1984 version never had that luxury. It often uses internal monologues to explain things, for instance, with the actors providing voice-overs to convey their thoughts. The tactic proves extremely jarring and disrupts the audience's engagement in the action.

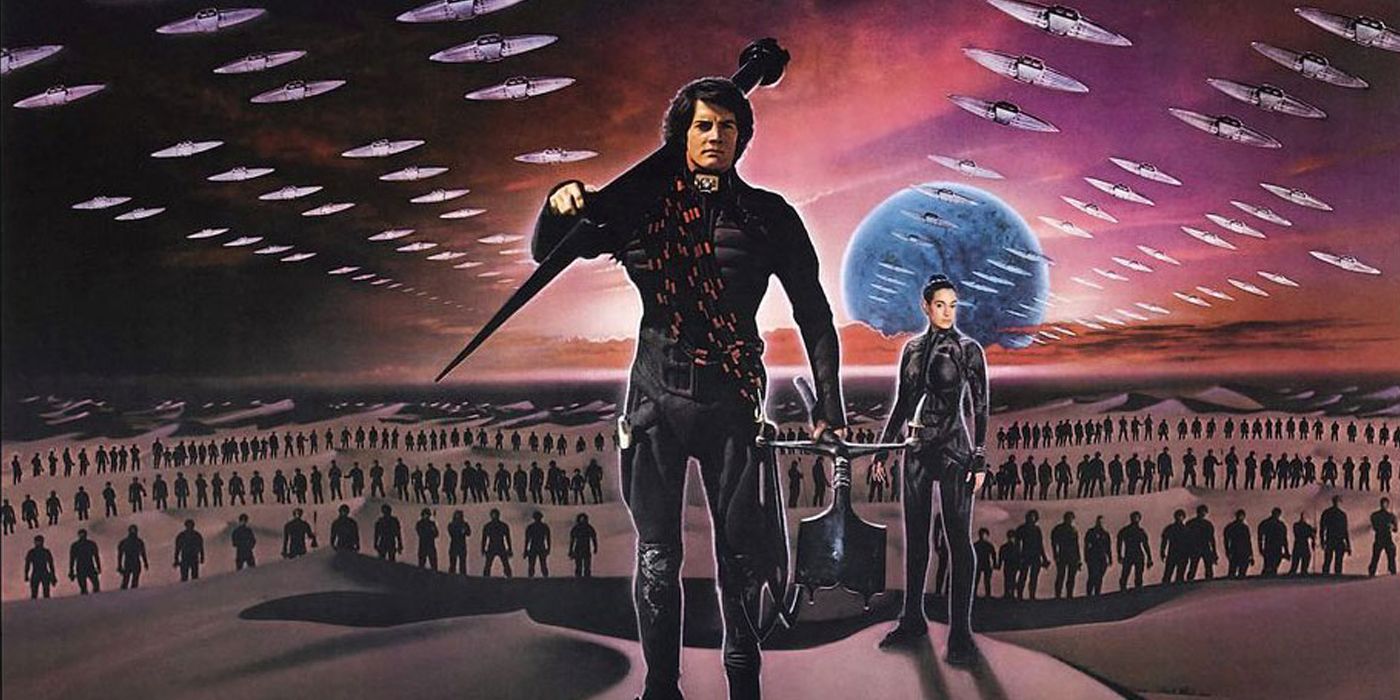

Lynch himself is known for the strange and surreal visuals in his movies, which hadn't appeared in such a big project before. In the case of Dune, he tries to convey how strange the human race might be in tens of thousands of years, and while the story features no sentient aliens, many of his characters are bizarre enough to qualify. Contrast that with Villeneuve's version, which emphasizes the characters' shared humanity and strives to connect them with the audience. Starship Navigators, for instance, appear as colossal whale-like creatures in Lynch's version, while the Navigators in Villeneuve's version are still humanoid in appearance.

Lynch's Dune Deviates From the Source Material

Perhaps most importantly to long-time fans of the series, Lynch makes changes to Herbert's details. That includes making Paul Atreides older instead of a teenager and de-emphasizing the story's focus on hand-to-hand combat. The book's "Weirding Way" martial art becomes a sonic weapon, giving practitioners the ability to shatter stone like superheroes. Baron Harkonnen becomes a bloated near corpse -- his face covered with rotting lesions -- and his scheming personality is replaced with senseless rants. The ending runs directly against the book's intentions, as Paul miraculously causes it to rain on the desert planet with powers he most decidedly did not possess. The book ends on a more troubled note, as the still-human Paul must grapple with the social implications of his messiah status.

That's all in keeping with Lynch's style: visually distorting good and evil into extremes. But it also becomes less an adaptation of Herbert's story than Lynch's vision of the far future, and while that holds potent temptations, it struggles with its most important task. Aside from alienating fans of the book, the world may simply not have been ready for a science-fiction epic of that scope and complexity, with the original Star Wars trilogy barely completed and multi-movie storylines all but unheard of. 1984's Dune simply required a different era of Hollywood to work, leaving both it and its creators stranded in the process.